“I Really Hope You’ll Come Around”: Remembering David Berman

Ely Vance | October 2019

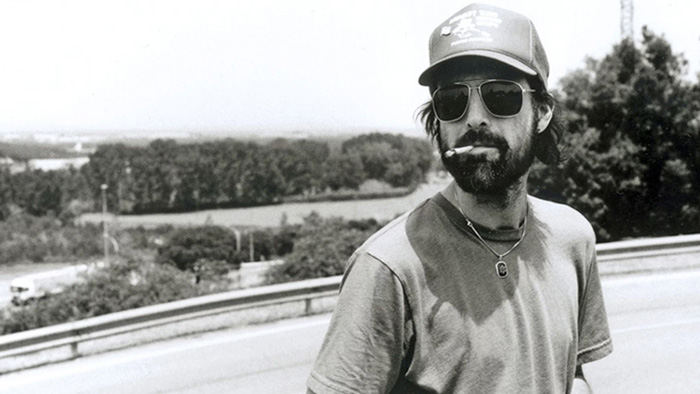

Few artists could do what David Berman could do. He brought his audience right next to him, onto the arm of a beat-up pull-out couch in Charlottesville or Nashville or Chicago, unflinching in his evocations of the absurd sea of noise we all sail upon, in his excavations of existential self-doubt, of daily self-hatred. The sloppy, staticky ’90s indie-rock scene that birthed his career couldn’t define him; nor could his time as a poet studying with James Tate at Amherst and publishing some of the most profound verse of the last quarter-century. Berman’s life transcends those fractious creative cliques because his art is transcendent. The artifacts we’re left with—the books and records that bear his mark, though cruelly insufficient in replacing the man who was with us until this August—are, of course, also a blessing. Even more so now that these songs and poems and spare bits of prose are all we have left, the closest any of us might come to conversing with the man in flesh.

And I had carried earnest, naive notions of just that, of meeting David Berman, until receiving texts from a friend on a Wednesday evening. Berman, after an absent decade, had released a new album this July under a new name, Purple Mountains, as gorgeous and unsparing as anything he’s ever made. It is without question a heavy listen, starkly detailing the collapse of his marriage and mental stability (from the first track: “Course I’ve been humbled by the void / Much of my faith has been destroyed / I’ve been forced to watch my foes enjoy / Ceaseless feasts of schadenfreude”), but it brings with it that unmistakable spark of desperate love: for language, for art, for all the people struggling along with him. His battles with addiction and depression had been in the public eye for years, but he always brought a wry half-smile, a generous joke, a romantic heart reaching out. His new band was to begin touring that weekend, and in promotional interviews he discussed openly how difficult it was for him to break out of the confines of his solitude and engage with the world, how hard he would need to push to get through it. In fact, he promised, though the thought brought him extreme discomfort, he would even stick around after every set to meet fans and make himself part of a community, however temporarily.

I’ve attended countless concerts in my time on this planet, but I don’t know if I’ve ever once felt the specific urge to wait and meet a musician after a show. It’s just not really my bag. But I found myself on my commute that morning listening to an old Silver Jews album, singing every word in my otherwise vacant sedan, and wondering what it would be like, in exactly one week’s time, to shake David Berman’s hand, to communicate to him somehow in a look, a couple sentences if I had to, what he had somehow communicated to me in the totality of his work, that certain sense of peacefully screaming across an empty highway ridge at sunset with an old friend, seatbelts off, speed slurring the landscape below like redundant philosophical musings at last call. The memorial listening night the venue held in the concert’s stead captured a sliver of that feeling: a room full of furtive glances towards a busy bartender, a lonely man huddled over a pinball machine, a VHS copy of the documentary Silver Jew looped on a tiny television in the corner, muted.

But that first night, when I knew that David Berman was dead, that I would never meet him, that no one would ever meet him again, I couldn’t think of much else to do but put on that same record and sink into the graceful charm of his brusque, nasal singing, his slow-dance through a sublime succession of sounds, spinning the words around again and again, and I couldn’t think of much else to think except how nice it would be to listen to him forever, to bask openly in the beauty of his breadth of feeling, to be so enraptured by the possibility of connection and love that you might lose the plot entirely and not even notice when they finally turn the lights out.

David Berman was a writer, an artist like no other. Just as we all are. May he, may all of us, find peace.

Ely Vance is a reader and writer from the Eastern Shore of Maryland who has worked in AWP’s Membership Department as an assistant and associate since the fall of 2017. He attained his BA from the University of Maryland, College Park, in English and American studies, minoring in philosophy and creative writing. When he isn’t reading or writing, he might be buying used records on Discogs or watching NBA highlights.