Dispatch from the Poetry Cave: On the Pleasures & Challenges of Coordinating the Kingsley & Kate Tufts Awards

Genevieve Kaplan | April 2019

A few years ago, I began working at Claremont Graduate University and, specifically, for the Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Awards. With my MFA and PhD in hand, having published a book and taught in various capacities, I stumbled into CGU’s orbit while seeking a more stable position, a job that aligned with my experience and expertise and would allow me to continue to participate in the literary community. While I was familiar with the awards and in awe of the work of the many fantastic writers—Susan Mitchell! Carl Phillips! Lucia Perillo! Cate Marvin! Beth Bachmann!—who had received the prizes, I didn’t know the awards’ history, their peccadillos, or their scope.

Here are the basics: Claremont Graduate University has been home to the Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Awards since 1992. Then-president John Maguire picked up the phone when Kate Tufts, a southern California resident, called CGU. She was looking to establish a national poetry prize in the name of her late husband, Kingsley. That early gift, funded by the sale of Kate Tufts’s family home—and bolstered by the energy and enthusiasm of Kate Tufts, local supporters, and the good people at Claremont Graduate School (as it was known back then)—has blossomed into the awards as we now know them: the $100,000 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, given annually for a book by a poet in mid-career, and the $10,000 Kate Tufts Discovery Award, for a poet’s first book.1

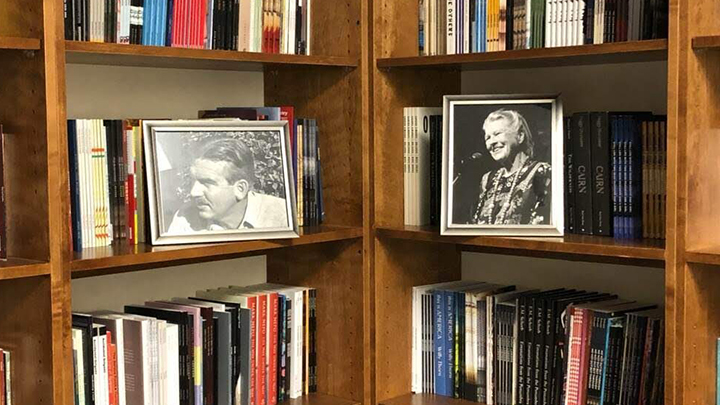

In my first weeks on the job I reveled in my sudden backstage access to these prestigious awards. The heart of the Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Awards is actually a series of rooms in the basement of CGU’s Harper Hall. Tucked away in a chilly corner near the mailroom are rows of poetry-filled bookcases, years of ephemera, and towering file cabinets. In the Tufts offices, which I affectionately refer to as the “poetry cave,” I found newspaper clippings, photos, and trust documents that give insight into how the awards had been established and run. Here, I encountered some surprising, useful, and new-to-me information:

- The Kingsley Tufts Award is meant to support a poet in “the difficult middle,” a writer “who is past the beginning but not yet reached the pinnacle of his or her career.”2

- The Kate Tufts Discovery Award “for a first book of genuine promise” was initially given in 1994, a year after the inaugural Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award.

- Early on, alongside published volumes of poetry, the Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Awards accepted submissions of unpublished manuscripts.

- When first established, the awards offered $50,000 (for the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Awards) and $5,000 (for the Kate Tufts Discovery Award); the amounts have since doubled.

- The final judging panel rotates, and the judging slots are dictated by the trust; the panel must include, for example, “a non-academic specialist in poetry who resides in Southern CA” (this year that honor belongs to Luis J. Rodriguez; past judges in this category have included Elena Karina Byrne and Kate Gale) and “the poetry editor of a general circulation magazine published in the eastern part of the US” (judges fitting this description have included Meghan O’Rourke, David Barber, and Paul Muldoon).3

- Awards celebrations have included “stars” who aren’t just literary: in 2002 Kathy Bates was featured as a special presenter at the Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Awards ceremony; at the awards ceremony in 2007, Leonard Nimoy read poems by winners Rodney Jones and Eric McHenry.

I also learned more about Kingsley and Kate, who were passionate literary types. Kingsley wrote short fiction and poetry while earning his living as an executive in the shipping industry. Among his literary successes, Kingsley could count stories that appeared in the Saturday Evening Post, Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, and Esquire; his poem “Life without Father” was published in the New Yorker in 1947. Kingsley and Kate held salons at their home, spending “years of evenings with friends making music and reciting verse.”4 According to seemingly unbelievable but oft-repeated CGU lore, Kingsley passed away during one such gathering: “On Christmas day in 1991, they were gathered with friends… sharing that year’s new poems. In the midst of the day, having just finished reading his third poem, with no warning, Kingsley died.”5 A legend-worthy end for this visionary man.

I never got to meet Kate, described as “a woman of . . . quick, candid, salty wit” and remembered fondly and frequently in the halls of Claremont Graduate University.6 She passed away in 1997. However, her and Kingsley’s legacy lives on. The pair wanted to “make a prize that really could send somebody off, give them time to concentrate.”7 They have accomplished their goal, establishing the Poetry Awards and enriching the lives and encouraging the writing of, as of this year, fifty-three poets. And, as a bonus, I had found myself a new job facilitating happiness and money for poets.

It’s a pleasure to see books I’ve been hankering after arrive on my desk, to encounter wonderful new books by poets I haven’t heard of or read before, and to be confronted with the massive scope of American poetry.

But first I had to find my way. Transitioning away from teaching and scholarship and more toward literary administration has been alternately difficult, exhilarating, tedious, and fascinating. I began my position in late March 2014. With the annual awards ceremony—traditionally scheduled for National Poetry Month in April—already planned and very quickly approaching, I didn’t have much time to think, react, or second-guess. Instead, I dove right into the event that is the pinnacle of our Tufts year. Meeting that year’s winners, Yona Harvey and Afaa Michael Weaver—two amazing poets whose work I loved—was a terrifying joy, knowing that I was about to guide them through a process I was myself unfamiliar with. I whisked them from hotel to interview to photo session to student meeting to—finally—the awards ceremony itself. Of course, Afaa and Yona weren’t our only visitors during this busy time. The Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Awards judges typically return for the ceremony to celebrate our new winners. That year, 2011 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award winner Chase Twichell (swoon! My Ausable Press hero!) served as our head judge, judge Jericho Brown attended and cheered, and other past winners and cool local poets—Claudia Rankine, Charles Harper Webb, Brent Armendinger, Hillary Gravendyk, Cecilia Woloch, Peter J. Harris—were in the crowd as well. It was probably a great party, but I was running ragged, trying to be in four places simultaneously, my head stuffed with event planning minutiae instead of poetry. That April was a beautiful blur for me, a month that I remember fondly but not specifically.

In the poetry cave, the year begins again after the awards presentation, as submissions start rolling in. Unlike other awards, the Kingsley & Kate Tufts prizes require no entry fee, and anyone—the poet, the publisher, your mom, a stranger—can mail in copies of eligible titles for consideration. When the books arrive, it’s wonderful. It’s a pleasure to see books I’ve been hankering after arrive on my desk, to encounter wonderful new books by poets I haven’t heard of or read before, and to be confronted with the massive scope of American poetry. We typically receive about 500 titles for both awards, and because we require eight copies of each (for distribution to our judges and screeners), that’s a lot of books. About 30% of my job is physically moving books—opening packages, shelving, moving from one shelf to another, repackaging, mailing, reshelving, etc. Not exactly what I thought I’d be doing with my advanced degrees! In all seriousness, though, the books are one of my favorite parts of working here—once all the titles are organized and shelved, it’s like being ensconced in my own private, free, poetry-only bookstore. A little paradise in the basement.

But there’s also the problem of those approximately 4,000 books that arrive annually. The screeners read all the titles and forward their top selections to the final judges, which leaves over 2,500 books here in the poetry cave, books I know that I have to move along before the next batch of books arrives again. I reach out to other professors, letting them know books are available. At Scripps College, Professor Warren Liu set up a poetry bookshelf outside his office for students to browse and enjoy. At the University of La Verne, Professor Sean Bernard gifts bags of books to his graduating poetry students. Here at CGU we hold an annual late-spring open mic reading and book giveaway; aside from getting to sit in the dappled shade of the School of Arts and Humanities backyard and listen to students’ poems, my favorite part of this event is seeing the readers’ eyes widen when they see the four tables of free books set out for them to choose from and take home. They fill their backpacks with poetry, and then they go back and fill their arms with books as well. But this doesn’t actually put much of a dent in the book mountain. I also arrange to donate boxes of books to public libraries, lending libraries, nonprofits, correctional facilities, literary groups, and more. It’s sort of thrilling to see these contemporary poetry books finding new, good homes, often with readers who might not have thought to pick up a volume—or that particular volume—of poetry to begin with.

Things tend to slow down a bit in the summer, and I typically take the summer months to pick up the chaos of spring, respond to questions from potential submitters, follow up with presses and poets as necessary, dream up new initiatives, and make sure everything is in place for the next round of reading and judging.

You’ve already heard about the rotating panel of final judges, but the hard work of reading all the submitted titles each year falls to the screeners. The screeners are local writers, typically poets who have published a book or two, who serve as first readers for a year. The books make their way to the screeners at the end of July or in early August, which gives the members of this three-person committee a few months to make their way through 500 books. It goes without saying that this is a monumental job. I served as a screener for the 2018 awards year, and even to me, someone regularly confronted with seemingly endless stacks of poetry, the task felt daunting. I began my work casually, taking a couple books home each day to read and consider. But by early September I realized that I’d never be able to get through all the titles at that slow pace. I stepped up to reading 10-15 books a day, which sounds like a lot, but it was also a beautifully immersive experience. Despite my years—and years—of formal education and generally voracious reading habits, that year I felt like I could really, truly say that I fully understood the scope of contemporary poetry. My fellow screeners, Nikia Chaney and Karen An-hwei Lee, and I met on campus in October, discussed the books we read, and determined the short list of about sixty titles to send to the final judges for their consideration. Then we went to dinner in town with awards director Lori Anne Ferrell and toasted our good work with Kate Tufts’s words, “May poets and poetry flourish.”8

In the fall the public gets to see some evidence of the hard work Emily Schuck, my student assistant, and I have been doing in the poetry cave. Every year our Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award winner returns for a week in residence in Claremont. This residency week is somewhat misnamed; rather than being a respite for the winning poet, CGU puts them to work. The week is a chance for the university to extend into the community, to show off our brilliant choice, to remind students and faculty and readers and audiences what an integral part of our lives poetry is and should be. Events vary from small to large: interviews, class visits, readings, workshops, exhibits, dinners, and more. 2018 winner Patricia Smith held a free generative poetry workshop for fifty local poets at the campus library. 2017 poet Vievee Francis wowed a crowd of over seventy listeners at the CGU art gallery. 2016 winner Ross Gay fell in love with an orange tree at the edge of the Scripps College campus. After a productive week of class visits and readings, 2015 poet Angie Estes trekked out to the Getty Museum and got stuck in traffic on the 405. No matter what happens during the week in residence, CGU and the surrounding community are left with the feeling that a fabulous poet has embraced us and our ways, just as we have embraced them. At one of the twenty-fifth anniversary events a few years ago, 2012 Kate Tufts Discovery Award winner Katherine Larson mentioned how nice it is to be part of “the Tufts family.” This phrase has stuck, perhaps because that is exactly what it feels like, especially during residency week--that these poets are, in fact, now family, and that they are always welcome with us here at CGU.

The screeners’ meeting and the week in residence are just a few parts of the long lead-up to the April awards ceremony. The final judges receive the short lists of books put forward by the screeners and meet virtually to discuss and determine the five finalists in each category. CGU announces the finalists each year in late January, and winners are selected from the finalist pool in late February or early March, when the judges fly out to Claremont to fight in person for their favorite poetry books. This year’s winner selections were the result of six hours of spirited deliberations on campus one Saturday in February. Luckily the judges had a couple hours to rest up before that evening’s “call-the-winner” dinner, an invitation-only evening that I think is both the weirdest and most fun thing that we do. About thirty of us, including the judges and screeners, listen to the announcement of the winners and then gather around a speakerphone. The president of Claremont Graduate University calls the year’s winners, giving them the good news while we clink our champagne glasses and cheer in the background. Sometimes there are joyful tears, sometimes joyful obscenities, sometimes joyful inarticulateness, but the poet always answers, and there is always joy. After the phone calls, we eat dinner together, and the judges read selections from the winners’ and finalists’ books during dessert.

No matter what happens during the week in residence, CGU and the surrounding community are left with the feeling that a fabulous poet has embraced us and our ways, just as we have embraced them.

The main event, the annual Kingsley & Kate Tufts Awards Reading in April, is a time to invite friends to celebrate our new winners and to introduce our new poets to the family they have now joined. Our awards events have had a few different iterations, but they are typically glorious evenings of pomp, circumstance, and poetry. Right now, they occur over the course of two days: we have a private awards ceremony and dinner celebrating our winners on campus the first night, and the second night is a free public reading and reception for the community. This extension of our awards events gives us time to record video interviews with our new winners as part of the “In the Poetry Library”9 web series, to offer our campus community the chance to hear the judges read their own poems,10 and to make the visit a little less hectic for our new winners (and for me). This year’s celebratory reading, featuring 2019 Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Award winners Dawn Lundy Martin and Diana Khoi Nguyen, is scheduled for Thursday, April 11, at the Huntington Library and Gardens. Join us! You won’t be sorry.

Sometimes people—poets, peers, job seekers, creative writers thinking about entering or avoiding academia—ask me about my job, usually saying something like “you have the best job” and/or “how can I get a job like yours?” I’m never really sure how to respond. Yes, my job is great. But, like any job, it’s also not-so-great. And being among poets and scholars in an administrative capacity, especially during awards season and the week in residence, when I spend more time on the job, is something I continue to struggle with. In other parts of my life, and during other parts of my week, I call myself a poet, writer, editor, teacher, professor, scholar, mentor, and/or colleague, but none of these describes my work at CGU. 11 My job here is to take care of the details, get things done behind the scenes, and essentially be helpful, cheery, and invisible. I’m generally happy to do this, but I suspect like many of us who work in these types of administrative positions, I tend to most acutely feel the loss of my own smart and creative self when I am busily promoting others. As awards coordinator, I can feel unmoored: like my education and experience no longer matters, like I suddenly have no agency, no authority, and no necessity. It can be a frustrating (and self-indulgent-feeling) challenge. I try to concentrate on the elements of working here that are more satisfying.

It’s been gratifying to see some of the impact I’ve made. Claremont Graduate University doesn’t have a program in creative writing, but it does have students, faculty, and community members who love poetry. Since 2012, CGU students have been running Foothill Poetry Journal12, and they’ve been going strong—meeting regularly, enthusiastically celebrating poets and poetry, and putting out consistently beautiful issues—ever since. Tapping into that enthusiasm and expertise, I started the Tufts Blogger-In-Residence13 program, hiring students each semester to write about poetry for a wider audience. CGU is part of a larger consortium which includes undergraduate colleges with strong creative writing courses and faculty, and we’ve been sharing resources. I’ve created, with CGU’s blessing and the expertise of CGU’s Director of Design, Gina Pirtle, an ongoing series of commemorative poetry postcards, essentially mini-broadsides. And I’m currently working with the marketing and communications team to start a podcast series, which will feature short readings and interviews with poets on campus and in the larger Tufts Poetry community.

These longer-term undertakings connect the awards with the larger campus community; they get students, faculty, and the public involved with all the cool things we do; and they share poetry resources across campuses and with the national poetry community.

It turns out that I love being around these projects in particular because they’re somewhat independent of the academy. The Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Awards and its friends around campus are not publishing and promoting poems, writing about poems and poetry, or interviewing poets because the university demands it—we are interacting with the creative world because we love it, and because, thanks to Claremont Graduate University, we have some resources we can devote to it. Down in the poetry cave, unencumbered by formalized academic constraints, I am allowed to return to the kind of celebration of the written word that made me fall in love with poetry to begin with. The work of the Kingsley & Kate Tufts Awards reminds me—and others—how poetry not only complements but is integral to our larger pursuits, in higher education and beyond.

Genevieve Kaplan is the author of In the ice house, winner of the A Room of Her Own Foundation’s poetry publication prize, and three chapbooks. She lives in southern California where she writes, edits, teaches, and coordinates the Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Awards.

WORKS CITED

- Wallace, Amy. “Love Is This: A Poetry of Bliss,” The Los Angeles Times, April 27, 1993, http://articles.latimes.com/1993-04-27/news/mn-27924_1_poetry-award.

- Miles, Jack. “Re: Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award and Kate Tufts Discovery Award,” January 29, 1995.

- “An Agreement Between Claremont University Center and Claremont Graduate School and Mrs. Kingsley (Kate) Tufts,” October 16, 1992.

- Maguire, John. “A Historical Note on The Kingsley And Kate Tufts Poetry Awards,” Kingsley Tufts Chapbook II, ed. Jennifer Jared, 2007, 3.

- Maguire, 3.

- Maguire, 1.

- Wallace, Amy. “Love Is This: A Poetry of Bliss,” The Los Angeles Times, April 27, 1993, http://articles.latimes.com/1993-04-27/news/mn-27924_1_poetry-award.

- In some prior years, the preliminary judging process was capped with a catered dinner on campus, complete with CGU bigwigs and local supporters. I remember my first such event: about 15 of us were sitting around a table at a catered dinner I had arranged on campus, when local writer and long-time Tufts supporter Larry Wilson demanded we all recite a poem from memory. Apparently this was tradition! Flummoxed me, I recited a short ditty by Jack Prelutsky while the screeners that year expertly consulted their smartphones to recall more moving and appropriate poems. This experience inspired me to (1) get a smartphone, (2) memorize more poems, and (3) gratefully acknowledge the screeners at later Tufts events in spring instead of putting them in the spotlight when they—literally—had just finished reading and discussing several thousand pages of poetry.

- Tufts Poetry Awards, “Media Library.” https://arts.cgu.edu/tufts-poetry-awards/media-library/

- Our judges tend to be amazing poets. Our current final judges are Khadijah Queen, Sandy Solomon, Cathy Park Hong, Luis Rodriguez, and head judge (and 2012 Kingsley Tufts poet) Timothy Donnelly. Past judges have included Brian Kim Stefans, Robert Pinsky, Allison Joseph, Carol Muske-Dukes, and Garrett Hongo.

- My job with the Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Awards is part time; happily, the stability of my ongoing position here allows me to pursue my other less-predictably-paying interests: teaching, writing, and creating.

- Claremont Graduate University. “Foothill Journal.” https://arts.cgu.edu/foothill-journal/

- Tufts Poetry Awards, “Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Blog.” https://arts.cgu.edu/tufts-poetry-awards/blog/