AWP’s 2017–2018 Report on the Academic Job Market

Jason Gray | December 2018

A year off from AWP’s annual academic job report finds the state of affairs in higher education, unfortunately, not much improved, and trends settling in to become industry standards.

Salaries & Benefits

First, a little good news. If you’re lucky enough to be holding tenure or a tenure-track job, your salary probably went up, and even outpaced the rate of inflation in the last year. Across the board, between academic years 2016–17 and 2017–18, according to the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) in its Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession, “average salaries for full-time continuing faculty members increased by 3.0 percent over the previous academic year, or by 1.1 percent after adjusting for inflation.” It’s worth noting, however, “Presidents of institutions participating in the AAUP’s Faculty Compensation Survey are paid 4.78 times more than fulltime faculty members, on average.” Also worth noting is that women are still earning less than 90 percent of what men earn at public universities.

According to the AAUP’s 2017–18 Faculty Compensation Survey, the average salary for full professors this year was $104,820, while associate professors had an average salary of $81,274, and assistant professors had an average salary of $70,791. The average salary for lecturers was $56,712, and the average salary for instructors was $59,400.

Looking at data from The Chronicle of Higher Education’s annual almanac, at public doctoral institutions of the highest research class, male full professors averaged $141,347, while female full professors averaged just 90.8 percent of that at $128,390. Looking at all ranks, men’s salaries were $107,899, while women’s were $85,444, only 79.2 percent of their male colleagues. Women fared better in the arts and sciences at baccalaureate institutions, earning 87.3 percent of what men did across all ranks ($67,009 vs. $72,611).

At private universities, women fared worse and better. At the highest research level doctoral institutions, women’s salaries were only 76.7 percent of men’s, but at the baccalaureate level, they were 90.3 percent. Unfortunately, the AAUP report explains, “No change in gender inequity is visible as faculty advance through the professorial ranks, indicating that equity is not likely to be achieved in the near future. Many institutions also have large gender pay gaps at the lecturer and instructor ranks.”

Inequality in the Professoriate

Who is making up our current cohort of students and current professoriate? Ruth Hammond, editor of the Chronicle’s almanac, summed it up this way: “Over all, colleges are getting closer to having a majority of minorities. In 2016, more than 43 percent of college students were members of racial and ethnic minority groups, an increase of more than six percentage points from 2010.” Faculty, however, remains 78 percent white, though new hires are only 72 percent white, so small gains are being made in increasing faculty diversity. Another bright note: “In the past year, more than a third of the people who became first-time presidents were female,” Hammond wrote.

Is the faculty of creative writing programs getting more diverse? There have been slow-moving positive trends, but given the decrease in new hires, it seems unlikely to improve soon.

Erica Dawson, Director of the University of Tampa’s creative writing program, says about their hiring, “We have taken the standard approach [to making diverse hires]. We always encourage, in our job ads, minority and female candidates to apply for our tenure-track positions. … I’d say, though, that we haven't been successful as I’m the last minority/woman who was hired for a tenure-track creative writing position. And that was in 2010.”

Women make up a higher percentage of lower ranks in the profession, which might imply they will move up and eventually replace men in the higher ranks, but they may also remain unpromoted.

Members of minority groups have increased their presence on faculties over the last few years. “Between 2013 and 2016,” the Chronicle sums up, “all sectors except two-year for-profit institutions increased the percentages of new instructional-staff hires who were members of minority groups. Two-year public institutions saw the greatest increase, of nearly six percentage points.” In 2016, at four-year public institutions, all minority groups were 27 percent of newly hired faculty, and whites were 71.5 percent. At four-year private institutions, minorities constituted 25.9 percent while whites were 72.6 percent.1 Small gains to equality are being made, but the disparity is exacerbated at the full professor level, which is 81.8 percent white.

A serious issue in hiring that is not reflected in data captured by the AAUP or the Chronicle of Higher Education is the consideration of groups beyond just gender and ethnicity. Problems with inequality extend to issues of age, disability, and sexual orientation. Unfortunately, the data isn’t there to discuss hiring trends for persons with disabilities, LGBTQ persons, or the age of people when they enter the market. This would be useful information to collect, though it would require self-reporting by candidates, as it is not data any institution can or should require. In 2017, the Chronicle of Higher Education reported on the lack of statistics for disability and hiring in higher education. The article states: “At the University of California at Berkeley, a recent Freedom of Information Act request indicated that of 1,522 full-time faculty members, 24—roughly 1.5 percent—are disabled. The National Center for College Students With Disabilities estimates that 4 percent of all faculty members have disabilities. These numbers are discouraging, given that 22 percent of the general population has disabilities.”

Earlier this year, Amir Haji-Akbari, writing for Inside Higher Ed, discussed disability hiring in higher education, remarking on his own experience as a visually disabled person. He writes, “When I began applying for academic positions in my field of chemical engineering in 2013, I disclosed the visual disability I have had my entire life. Throughout my academic career, my disability had never impeded my pursuits. … But as I applied for faculty positions, the doors seemed closed. Frustrated, I stopped disclosing my disability status on applications and immediately started getting calls and campus interviews. Even then, multiple colleagues advised me to conceal my visual disability in order to avoid hurting my chances of getting a job.”

Workers are still fighting ageism, too. Recently, an American University professor won a lawsuit against the institution for being denied tenure due to her age. Loubna Skalli Hanna, a Middle East scholar, was in a tenure-track position, and was recommended for tenure by her committee and dean, but the provost denied her tenure. Hanna’s lawyers “questioned [Provost Scott] Bass about his own scholarly work on aging and the role of older workers in a market economy. They said he had approved tenure for younger candidates with lesser publication records.” The jury agreed with Hanna and she was awarded $1.33 million.

Tenure & Adjuncts

As of fall 2016, four-year public institutions had the highest percentage of faculty with tenure or on the tenure track, at 44 percent. That means, of course, that 56 percent of faculty members were not. Four-year private institutions had an even lower rate of 35 percent of faculty in tenure lines. The rates including all types of institutions brought the numbers to 33.8 percent tenured or tenure-track and 66.2 percent of faculty who were not.

The disturbing trend of increasing use of adjunct and part-time labor shows no signs of stopping. The AAUP reports that in 1995, tenured and tenure-track faculty made up 34.4 percent, and non-tenured full-time and part-time 46.8 percent. In 2015, it was 29.6 percent and 56.7 percent, respectively.

Pay for part-time teachers is still below the level recommended by the Modern Language Association. The association suggests a minimum compensation of $10,900 for a standard three-credit-hour semester course. But the AAUP data shows that the median part-time per-course salary is $10,739 for doctoral institutions, $5,869 for master’s institutions, and $5,183 for baccalaureate institutions.

Colleges and universities lean heavily on adjuncts. New graduates are still trying to make it work, cobbling together courses at multiple locations, with low pay and most likely no benefits. “Only 5 percent of reporting institutions indicated that they offer all part-time faculty members benefits,” reports the AAUP. “Another 33 percent of reporting institutions offer some benefits to part-time faculty.” I asked several program directors what their students were considering as far as teaching careers, and though few responded, those that did suggested that despite the long odds, graduates are still taking up adjuncting in hopes of gaining a full-time position down the line.

Even with full-time work, those who are not tenured and are working on a contingency basis, usually in annual contracts, are at risk to budget cuts and the whims of administrators. As the AAUP report says, “While contingent faculty members are often highly qualified and dedicated teachers, their tenuous working conditions affect students. By definition, contingent faculty lack protections for academic freedom. This means that they are vulnerable to dismissal if readings assigned or ideas expressed in the classroom offend a student, administrator, donor, or legislator, or if students don’t receive the grades that they want. Thus, the free exchange of ideas may be hampered and students may be deprived of the debate essential to citizenship and of rigorous evaluations of their work.”

The loss of academic freedom is no joke. Inside Higher Ed surveyed provosts about the state of higher education and found that “[p]rovosts in the survey were much more confident of the security of free speech on their own campuses than they were about its status in higher education as a whole. On their own campuses, 19 percent of provosts said free speech was very secure, and 61 percent said it was secure … But asked about college campuses generally, 51 percent said that free speech was threatened, and 8 percent said it was very threatened.”

With tenure in decline, as well as shared faculty governance, it will be more difficult for academics to provide thoughtful and challenging education to their students.

State & Federal Funding

Much of decreased budgets for university departments and increased used of part-time labor can be traced to state and federal funding trends, which have walked hand in hand with increased devaluation of higher education in the political and public conscious across the country. A recent Gallup poll found that high confidence in higher education had dropped from 57 percent to 48 percent from 2015 to 2018.

According to Humanities Indicators, “[i]n all but a handful of states, appropriations for public higher education (including appropriations by local governments) were lower in 2015 than in 2008.... In 20 states, appropriations fell 20% or more. Louisiana and Alabama had the steepest declines, 38% and 41%. The median change among states was a 19% decline. Nationally, state/local investment in public higher education was 15% lower in 2015 than just before the recession.”

While appropriations ticked up after 2015, as Inside Higher Ed reported this year, funding is still down by large amounts. “After adjusting for inflation, state appropriations per full-time equivalent student are about 10 percent below their levels of a decade ago and down 8 percent from 25 years ago. Net tuition per full-time equivalent is up 36 percent over a decade and up 96 percent over 25 years.”

Even those with tenured jobs are now at risk of loss of retirement plans. “As of 2016–17, only about half of state pensions were sufficiently funded,” reports the AAUP. “Several states require new faculty to support underfunded pensions with their own retirement contributions. For example, in Ohio 1.5 percent of an employee’s salary goes to fund past service liability (underfunded pensions), and in Illinois, 25 percent of the retirement contributions of employees hired after 2011 fund pension benefits for employees hired before 2011.”

The Great Recession gutted many institutions’ endowments, and lower appropriations from states and the federal government have led to unprecedented budget constrictions. AAUP’s report offers a rather chilling summation:

States are dismantling higher education through severe budget cuts, by eliminating the protections of tenure, and by shutting down institutions without consultation with faculty members or the communities that they serve; at the federal level, the recently passed tax bill will now treat the largest endowments at nonprofit private higher education institutions as a source of revenue. At the time of this writing, the key piece of federal legislation regulating most aspects of higher education, the Higher Education Act, is up for reauthorization before the US Congress. In its current form, the legislation under consideration would roll back consumer protections for student borrowers, increase federal funding to for-profit colleges, and eliminate the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program.

The Quantity of Jobs Available

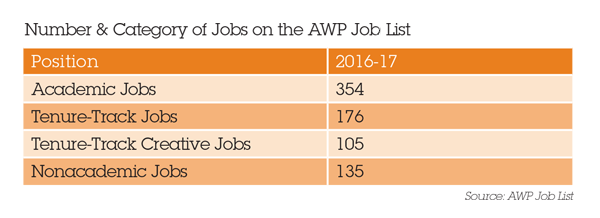

AWP’s Job List for the academic year 2017–18 had 316 listings for a total of 354 positions. This set of jobs can be further broken down into 178 non-tenure-track positions and 176 tenure-track positions. This is a steep decline from previous years, a decline echoed by the Modern Language Association’s own job report. The MLA had 851 listings in the past year. “In 2016–17, the decline in the number of jobs advertised in the MLA Job Information List (JIL) continued for a fifth consecutive year. The JIL’s English edition announced 851 jobs, 102 (10.7%) fewer than in 2015–16; the foreign language edition announced 808 jobs, 110 (12.0%) fewer than in 2015–16.” This is not only a continued decline over the past five years, but it has fallen under the previous low point in 2009–10, which was attributed to the Great Recession. So, while salaries have recovered from what the recession took away, the number of positions available has not.

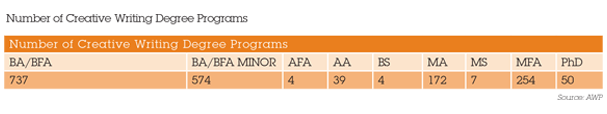

And just how many graduates are there who might be competing for these jobs? The number of creative writing programs has increased from the last report by a handful, and so have, we can assume, the number of graduates. A notable exception to this is the steady state of PhD with creative writing emphasis programs at 50. Not everyone wants a teaching job, but many do, and the competition continues to be fierce.

Colleen Kennedy, PhD in English Renaissance Literature, who is currently on the job market, reported:

During the four years I have been searching, there are fewer positions each year and they are both: 1. More generalist positions (not necessarily a bad thing) as they seem to want to hire someone who can teach either Medieval or Eighteenth Century in addition to English Renaissance Literature or in a secondary (or even tertiary) unrelated English literary field

2. Each year there is a new sub-focus for the overall field of English Renaissance literature. Currently, it is Critical Race Theory and Renaissance Literature. During the last few years, there had been a focus on Digital Humanities, Transatlantic Studies, and Book History.

This follows from the last academic jobs report where Ira Sukrungruang’s comments on the rise of the generalist: “Gone are the days of the single genre author.”

Adam Vines, associate professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, does not “pull punches with [his] students” about pursuing a graduate degree in creative writing. His advice would be good for creative writing programs to follow: “I tell them that the job market for CW is more competitive than any other profession and that they will most likely never get a tenure-track position. We talk about skills and progress instead of degrees that will fit into a slot for a teaching position. I tell them to apply only to fully-funded programs in an affordable city they like and to think of an MFA or PhD program as a paid residency” (emphasis mine). As Ohio State professor Michelle Herman said in the last edition of this report, even a PhD is no longer a guarantee of a job, nor has it been for some time.

Current students and new graduates would do well to look into the AWP series on Life After the MFA, which links to some useful resources for finding jobs, as well as crafting a CV and requesting letters of recommendation.

University of Tampa’s creative writing program director (and AWP board member) Erica Dawson’s advice for graduates on the market: “Focus on that cover letter. Do not be shy about flexing your skills and accomplishments. Tell the committees what you can bring to their classrooms and campus communities. Tell them how you can help them move forward with their mission. Be confident. Convince them they need you.”

Of course, some of those who go into an MFA or PhD program in creative writing might be coming from another career where they have skills that might take them back there, but many are coming straight from college or not long after, and finding work in alternate fields might not be so readily available.

So, what are a graduate student’s other options? There are many nonacademic jobs that writers and academics would do well in. AWP’s Job List published 124 jobs (135 total positions) like these last year. The MLA has a helpful primer by Sarah Goldberg on how to prepare for a career outside of academia. The primer “provides suggestions for how to gain professional experience and prepare for a possible career outside the academy. However, the advice will serve you well for life inside the academy, too,” writes Goldberg. “Your job search need not be an either-or situation; many people conduct tandem searches, and the preparation you do for one search will also be useful for the other.”

In her article for the MLA’s Profession, Beth Seltzer analyzed 100 recent job ads after asking herself the question, “If academic job ads routinely ask for a wide range of skills, why does graduate school training often devalue the activities that would build these skills?” Seltzer arrives at a set of thirteen transferable skills from academic to nonacademic positions, and proposes graduate programs adapt to help students prepare for work outside the academy: “working for a university (which is, after all, what many graduate students are doing during their studies) could offer ample opportunities to build the experiences needed for both faculty and nonfaculty jobs—if graduate programs are willing to make this type of training a priority. The main obstacles are cultural rather than structural. It will take some reprioritizing for graduate programs to acknowledge, train for, and help graduate students appreciate the full range of humanities labor, much of which has traditionally been invisible or undervalued.”

Along those same lines, Stacy Hartman has a useful post about transferable skills and how to talk about them at the MLA blog, with documents “to help you identify your skill sets and describe them in ways that make sense to potential employers.”

Some MFA and PhD programs do have such training, or at least offer opportunities for students to explore alternative career paths: The Publishing Laboratory program at the University of North Carolina–Wilmington is a terrific model, as is the Publishing & Writing program at Emerson. Schools offering courses in literary publishing or editing are doing an enormous service to their students.

The news isn’t great, nor has it been for a long time. Awful trends of inequity, inequality, and poor representation persist despite small steps taken in the right direction, and institutional dependence on adjunct teachers continues unabated. Nevertheless, there are resources out there, including the MLA, that are addressing the need for graduates to think outside of academia. So, while we continue to encourage academic programs to make positive changes, everyone on the market should be taking a broad view of the academic job landscape and all the challenges it entails.

Jason Gray is the author of Radiation King and Photographing Eden. He has also published two chapbooks, How to Paint the Savior Dead (Kent State UP, 2007) and Adam & Eve Go to the Zoo (Dream Horse Press, 2003). His poems have appeared in Poetry, The American Poetry Review, The Kenyon Review, Literary Imagination, Poetry Ireland Review, and many other places. Besides writing, he spends time taking pictures of things.

NOTES

- The remainders of 100 percent in both sets of data were those reporting two or more races.