Hemingway's Workshop:

What a Writing Program Can Offer You

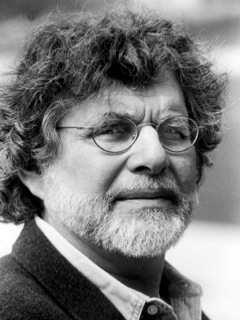

Alan Cheuse | July 2012

About a dozen years ago—it was the year Jhumpa Lahiri won, I can place it that way—I served as a judge for the PEN/Hemingway Award for First Fiction. The award ceremony took place in Boston on a windy Sunday afternoon at the John F. Kennedy Library (where the Hemingway papers are stored), a beautiful building near the harbor that gave the appearance of a ship under full sail heading into the wind.

Lahiri had arrived early, accompanied by a full brace of family members, many of them women and splendid in their festive saris. Everyone felt so proud about her winning this coveted prize! And who wouldn’t, an apprentice writer rising with a first book to the attention of general readers?

Before the public arrived, the director of the Hemingway collection held a gathering for the jurors, their guests, and the winner and her friends and family. Present was Patrick, seventy one years old at the time, Hemingway’s second son and the first child of the writer’s marriage to his second wife, Pauline. He and his wife had flown in from Montana to celebrate the annual award.

Over a glass of wine, the files with his father’s manuscripts stacked in the shelves behind us, we talked about his father, his own life in Africa (he worked as a hunting guide for many years), and the highlights of the day. He said he had read Lahiri’s work and that she was a good young writer. I said that I agreed. And then, all too forthrightly, I said that there were many good young writers around these days, and offered that his father might think it odd, the writing situation at the moment, with so many erstwhile fiction makers enrolled in MFA programs around the country.

“No, no,” he said, “it wasn’t that way at all. My father attended the University of Paris.”

“Really?” I had read a couple of biographies and nowhere did I see a mention of this.

“It’s true,” Mr. Hemingway said. “He took tutorials there—in Paris—from Gertrude Stein, from Sherwood Anderson, from Ezra Pound.”

“Of course!” Now I saw it. That circle of brilliant and intense and enormously provocative and productive writers, that was Hemingway’s writing program. He apprenticed himself to them, and before too long began writing the work that we know as the early stories.

So even young Ernest Hemingway needed editorial guidance and aesthetic instruction is the moral I took away from that little conversation. Which reminded me of Emerson’s suggestion in his “American Scholar” essay that even our greatest geniuses, Plato, say, and Aristotle, where once just young men in libraries. And if the proud, irascible, cantankerous young Chicago expat could take instruction from masters in the art of prose—at least when he was first starting out as a writer, because we know that soon thereafter he would accept instruction from no one without spitting bile back at him±why not the rest of us, who need it a hell of a lot more?

Here is where you have to take a look at what is available to you, when you are yourself first starting out. Ideally, yes, you should go to New York or Paris or Prague or Mexico City and apprentice yourself to a few geniuses and take from them what they offer. Short of that, you can scrutinize the list of instructors at various MFA programs around the country, see whose names you recognize, read their work and see how it strikes you, and make your judgment about where you would like to go based on that decision foremost.

Money, of course, will be an issue. But it should not be the paramount issue. Would you like a fully paid two or three years in a program with instructors whose work you did not admire? Or would you think it worthwhile to apprentice yourself to a few first-rate writers in a program that either can’t give you much financial help or chooses to give it to others in your group?

Writing is difficult, and the writing life when you first start out is difficult, and then gets more difficult before, if ever, it gets a little easier. An apprenticeship with someone who has a lot to give you means you may do some heavy lifting and sparks may burn you because you’re standing close to the fire. But that is the best system we seem to have come up with in the last sixty years. And while the major circle of apprenticeship comes in the serious reading you need to do in order to master the great techniques of the masters—something you can with some effort make time to do on your own—the other great circle comes with proximity to those contemporaries who seem to be just slightly ahead of us all.

Whatever the cost, you should take workshops with Richard Ford or Nicholas Delbanco or Richard Bausch or Jennifer Egan or Michelle Latiolais or Ron Carlson, or somehow find a way to take from more than one of them, or from some of the not yet nationally branded writers whose work you discover—with sparks flying—as you look into where you might want to apprentice yourself.

Apprentice yourself, yes, like some young medieval smithy, as Delbanco once suggested. To learn technique. To learn to recognize your strengths and weaknesses, build up the former and efface the latter.

As you might have in Paris, in the twenties, in spring, with Gertrude Stein telling you things about your sentences, your verbs, which you might not want to hear but which could change everything.

Alan Cheuse teaches writing at George Mason University and spends his summers teaching writing at the Squaw Valley Community of Writers. Cheuse earned his Ph.D. in comparative literature with a focus on Latin American literature from Rutgers University. He has been reviewing books on NPR’s All Things Considered since the 1980s.